Aging with Your Art

This is a tough topic to cover, because it’s hard to touch on it without seeming like you’re belittling your earlier works, something few writers/painters/general artists want to do. Yet it is one I think merits discussion, especially as the digital landscape has made it so far fewer books are every truly “out of print” or even hard to find.

Let’s go ahead and lay down what I’m talking about, for anyone who wasn’t tipped by the title. We’ll use me for an example, mostly because I’m more comfortable discussing my own career growth than someone else’s. I release 3 novel-length books per year. That means as of the writing of this blog (2019), I’ve released 18 books in the 6 years since I started as a writer, and that’s ignoring all the novellas, site stories, and other content.

Point is, I’ve done a lot of writing in the last decade. As you might expect, doing a thing for hundreds/thousands of hours, I’ve gotten better at it. At the story-telling, yes, but also just in the simple nuts and bolts of creating a book. Moving into audiobooks made me way more conscious of dialog tags, including beta-readers highlighted my tendency to overuse a phrase in a book, I could go on for a while. All of which is a good thing, mind you. If I’d been doing this for six years at that pace and couldn’t find any areas where I’d grown, it would probably be time to consider a career change.

All of which was a very long lead-in to address the main subject of today’s blog: How to age with your art. Because the curse of being indie is that it can be very tempting to go back, knowing what you know now, and fiddle with things a bit. A tweak here, a change there, you’ve learned so much, it would be easy to fall back into. Outside of basic, foundational corrections (Usually large amounts of typos and formatting) you’ll largely want to resist that urge. Trying to update your older works is a poor use of your time and energy that could be put toward making something new, plus risks inadvertently losing the charm you captured on your first go through. Most of all: you want the story to be consistent, whether a reader picked it up today or three years ago. They need to be able to discuss the same tale, and the more you tweak, the more you risk wrecking that.

So, if constant tweaking is out (it is) then how do we as creators cope with seeing something and resisting the urge to reach our hands in and polish it a tad more? As with the majority of such topics, there really is no hard and fast rule, but in talking with other authors I’ve found a few tactics that work for folks.

The biggest of which is to remember that it’s a good thing you can see flaws you missed before. That’s why I touched on it above, it’s part of the common vernacular in these talks. You have to mentally contextualize it as growth, rather than failing to spot a typo or the same adjective twice in one sentence. Keeping that proper mindset at the forefront not only halts you from slipping down a few dark mental slopes, it also changes the way you react to noticing old errors. Rather than dwelling on them, they become kicks in the pants to go double-check your current WIP and make sure you’re not making the same mistakes. If you’re always striving to improve, then you’ll spend your life running into this issue, best to put it in perspective early on.

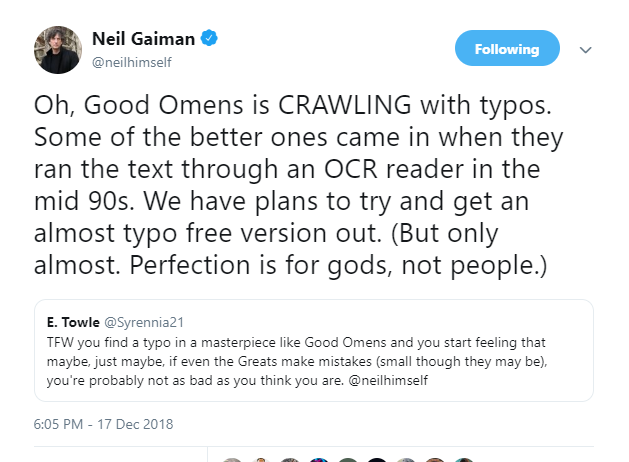

The next bit is to remember that no book is perfect. I struggled with this for a long time, and still do to this day, every typo I find is like a needle in the skin. But eventually, you have to make peace with imperfection. I even keep this Neil Gaiman tweet saved to my desktop, a reminder for when my brain tries to get overly hung up on some unattainable ideal:

Here’s a good hint, if the creative team of Neil Gaiman, Terry Pratchett, and all the creative resources that entails couldn’t create a book with no errors, the rest of us probably won’t pull it off either. It’s okay that your older books have some flaws. Your current ones will too. Sometimes, that’s even a good thing, more than one idea has started as an accident.

Ultimately, the final tip I have is the one I lean on the most: looking at the story. Even if I didn’t catch every last issue, so long as I can still look at the story being told and feel good about the work, I’m okay. Your form will get refined, your style more skillful, but assuming you got across the ideas and feelings you were putting on the page, there’s nothing to feel bothered about. Doing the best you can at the time is always something to be proud of.

It’s entirely natural to want to put out the absolute optimal product you can as a writer. That’s a good feeling, hold onto it and keep it close, especially in the hard times. However, once a book exists, you have to let it find its own way. Take your lessons and put them into your next project, which itself will have eventual flaws, and that will be okay too. So long as you’re putting all you have into a work, the effort itself will stand the test of time.